The London Metropolitan Police Service initiating the use of Live Face Recognition technology, as they’ve done recently , is another step in the by-now inevitable erosion of our traditional notion of privacy. The EU dropping their ban on facial recognition — devolving the issue to its member states — is yet one more.

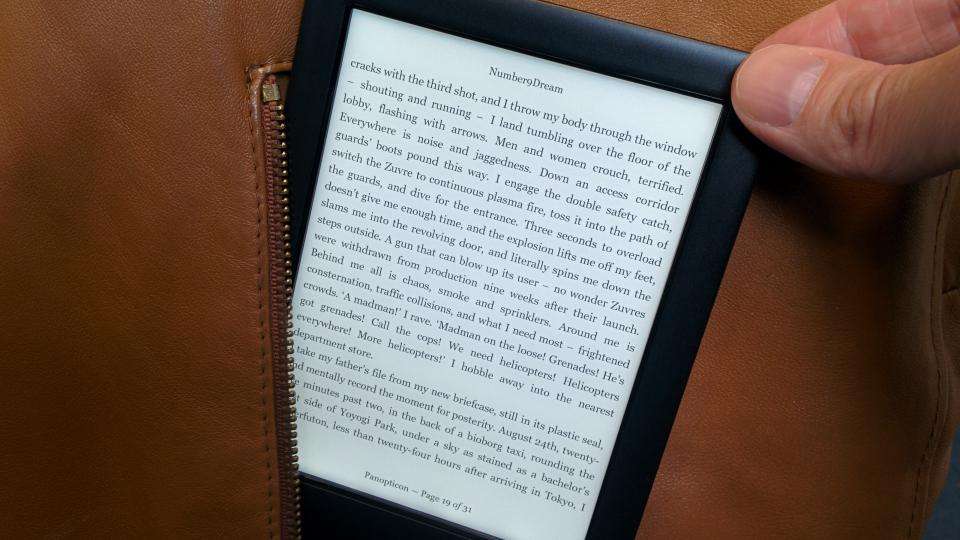

In China, face recognition cameras have widely replaced ID checks, and are in public use to catch not only serious criminals but jaywalkers, and to shame people spotted walking down the street in pajamas by broadcasting their names and images. Soon such phenomena will extend far beyond China, it seems likely.

Several US states have banned police use of facial recognition tech, and some EU states may follow — but it seems improbable that these bans will last. After the first few widely publicized horrific occurrences that would arguably have been preventable by facial recognition tech, public opinion is almost sure to reverse.

David Brin, in his 2005 classic book The Transparent Society , argued that we are inevitably headed in one of two directions: Surveillance or sousveillance. Surveillance meaning Big Brother watches everyone, and sousveillance meaning everyone watches everyone. What we are seeing now is a subtle combination of the two. Increasingly people are posting details of their personal lives online for all who care to see; at the same time, government and corporate monitoring of our communications and movements grows ever more pervasive.

There seems almost an iron law of adoption at play here. It may be stalled a few years here or there by privacy qualms, but in the end facial recognition capability has so much value for doing good, preventing danger and promoting efficiency, it’s hard too see it not being rolled out widely everywhere. In a decade, wariness about facial recognition will seem about like wariness about picture IDs seems today. People will put up with the police and spy agencies tracking their movements because it’s so convenient to buy a cup of coffee and enter the subway without dealing with scanning cards, and so reassuring to see terrorists and baby-nappers nabbed by robocops guided by camera footage.

Our only possible counter-move

What needs to be done, if we care about perpetuating what limited participatory democracy we have today and preventing or at least delaying the advent of techno-fascism, is to counterattack in judo style.

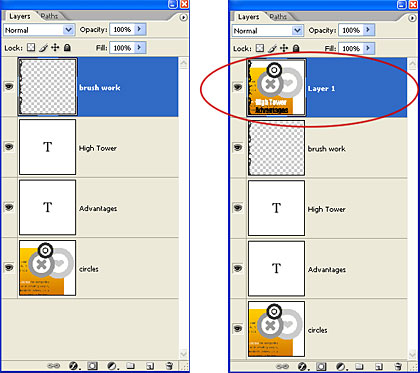

Don’t try to block the advent of facial recognition and other AI surveillance tech — rather, accept it’s coming and take control and ownership of it. Every image of you, snapped by anyone’s camera, should have a hashcode indicating your identity coded into it. You should then have the legal rights to track every image of yourself and observe what it’s used for.

Wearable tech pioneer Steve Mann has called this “Meta-veillance” — the technology of seeing sight itself, of watching the watchers, whomever they may be.

If the infrastructure and legal right for metaveillance were in place, a software ecosystem would evolve around it — and we would all have transparency and control over use of our images and other personal data. Of course, abuses would exist, by government agencies and private parties — but these would be illegal acts and redressable via the court system.

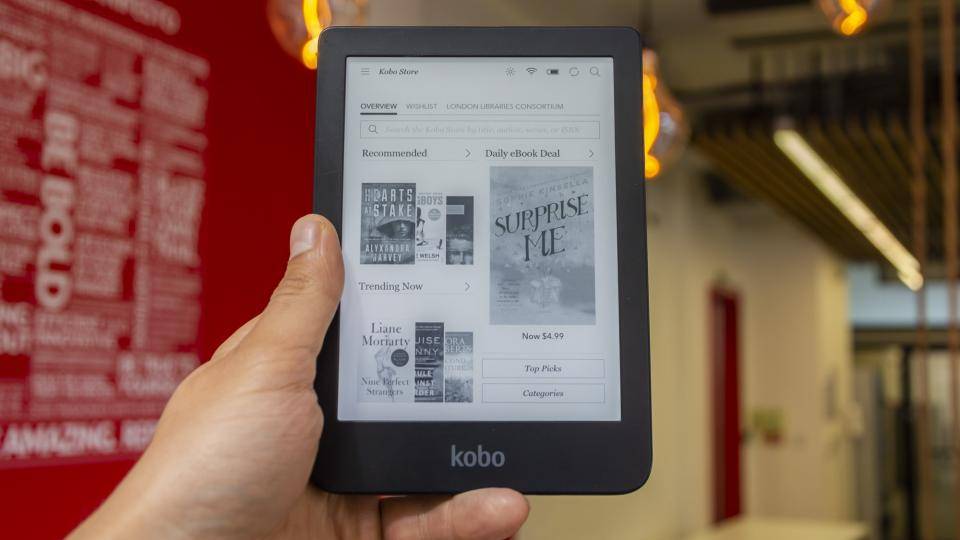

The blockchain and AI technology exists to enable us to take control of our own images and other personal data. But there are obvious organizational obstacles to putting this sort of democratic metaveillance solution into play. At the moment police and spy agencies and advertising companies understand the potential of facial recognition and other monitoring technologies much better than the average person, and they will use this information asymmetry to their advantage. But as the tech rolls out more and more widely, one can hope for broadening appreciation of the scope of potential solutions to the issues it poses.

If we can’t get it together to build and legislate a framework for democratic metaveillance, the outlook for our basic civic freedoms looks bleak.